|

|

|

|

District Significance During colonial rule, manufacturing in America was restricted by England. The New World turned over raw materials to the mother country for manufacturing articles, which the colonists had to buy at advanced prices. Thus, the United States was still largely agrarian, with a few small industrial and manufacturing enterprises, when it became a new nation. It was dependent upon England for basic necessities and isolated from the developments in industrialism that were taking place across Europe.

As the nation's first Secretary of the Treasury, he put into effect an interlocking system of law, finance and incentives that joined the men of commerce and finance behind the federal government. He saw the advantage of pooling men's resources, putting power in the hands of capitalists, to advance America's industry, and, thus, the nation itself. This stimulated economic development, which in turn fortified the government. This new "capitalism" enabled a new way of life for Americans. No longer did one have to be born or marry into high society to become wealthy. No longer did wealth have to be tied to land ownership. Hamilton’s mission was to widen man’s possibilities; to work for oneself through the marketplace. Each individual could prosper if he proved energetic and hard working. He gave Americans a chance to become self-made and inspired millions throughout the world to reach for what came to be known as the "American Dream." On December 5, 1791, Hamilton delivered his famous "Report on Manufacturing" to Congress. It is regarded as one of our ablest treatises on government encouragement of manufacturing. In this report, Hamilton explained his plan for a great industrial community that would produce articles of prime necessity, particularly cotton goods.

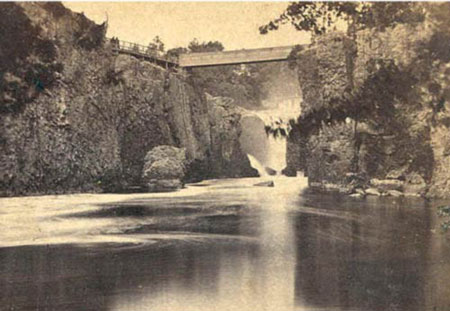

Hamilton selected the land surrounding the Great Falls of the Passaic River in the State of New Jersey for the proposed manufacturing settlement. The enormous height of the falls, 77 feet, and the surrounding terrain had characteristics that were essential for the utilization of waterpower at that time. Hamilton had seen this place while serving under George Washington during the Revolutionary War and visualized the abundant waterpower behind the great cataract. Hamilton also selected New Jersey because the legislature of that state was willing to give the S.U.M. many special privileges that were not normally granted to private corporations. The S.U.M. was granted a charter on November 22, 1791 by Governor William Paterson and the new town was called Paterson. The S.U.M. purchased for $8,233.53 a tract of about 700 acres adjoining the Falls. They took into consideration the fact that artificial reservoirs could be easily formed at the several lakes or ponds at the headwaters of the stream's tributary to the Passaic. This would serve to retain a supply of water for dry seasons. Other important factors were the nearness to the New York and Pennsylvania markets and to tidewater. Construction of a raceway system began in 1792. It was the first attempt within the United States to harness the entire power of a major river.

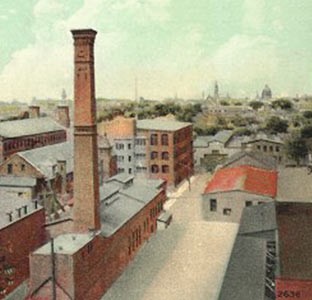

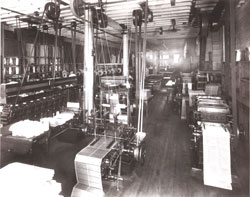

The Society made major additions and alterations in the raceway system throughout the first half of the 1800's. In its ultimate form, the raceway was capable of developing over 2000 horsepower. Land along the raceways was subdivided into industrial tracts that were sold to industrialists for building mills. Paterson, along with other manufacturing centers that utilized large waterpower systems, eventually created great economic wealth from textiles, paper and machinery. One of the richest industrialists of Paterson was Jacob S. Rogers. He inherited the Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works from his father, Thomas Rogers, whose inventive mind and perfectionist ways had made Rogers locomotives world-famous for quality. By 1866, the company occupied four mill lots on the upper tier of the canal system and was the largest locomotive plant, if not the largest company, in the Paterson area. When Rogers died in 1901, he left almost his entire fortune to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Countless masterpieces throughout the museum bear his name as donor - works by Van Gogh, Velazques, Degas, Bellini, DiPaolo, Bruegel. Rogers’ name can be found on significant works in just about every collection of the museum: European, American, Egyptian, Near Eastern, Far Eastern, Greek and Roman, Islamic, Medieval, Arms and Armor, and European Decorative Arts.

|

Changes to this status quo situation were envisioned by Alexander Hamilton, the

first Secretary of the Treasury, who saw it as his task to introduce these

industrial developments to the new government. He stated to President George

Washington and the cabinet that "America, to be free from British

influence, must be industrially free."

Changes to this status quo situation were envisioned by Alexander Hamilton, the

first Secretary of the Treasury, who saw it as his task to introduce these

industrial developments to the new government. He stated to President George

Washington and the cabinet that "America, to be free from British

influence, must be industrially free." Hamilton put his encouragement of manufacturing program into effect and began to

provide an attractive example. With the backing of several entrepreneurs in New

York and Philadelphia, he planned and organized the largest manufactory in the

United States and the first large business corporation in America. It was called

the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.).

Hamilton put his encouragement of manufacturing program into effect and began to

provide an attractive example. With the backing of several entrepreneurs in New

York and Philadelphia, he planned and organized the largest manufactory in the

United States and the first large business corporation in America. It was called

the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.).  Several combinations of engineering plans were used to create the raceway

system, including one by Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the city planner who designed

the layout of Washington D.C. Two years later, Peter Colt brought water to a

S.U.M. mill and began to turn out cotton textiles.

Several combinations of engineering plans were used to create the raceway

system, including one by Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the city planner who designed

the layout of Washington D.C. Two years later, Peter Colt brought water to a

S.U.M. mill and began to turn out cotton textiles. The Great Falls / S.U.M National Historic Landmark District exemplifies the

history and decline of industries in early nineteenth-century in the United

States. Paterson became a center of industry because of its vital relationship

to water. As that dependence was replaced by electricity, industries moved away

from these power centers. What remains is an outdoor museum, an island in time,

where we can experience an important part of America's early industrialist

period, one that was reliant on waterpower.

The Great Falls / S.U.M National Historic Landmark District exemplifies the

history and decline of industries in early nineteenth-century in the United

States. Paterson became a center of industry because of its vital relationship

to water. As that dependence was replaced by electricity, industries moved away

from these power centers. What remains is an outdoor museum, an island in time,

where we can experience an important part of America's early industrialist

period, one that was reliant on waterpower.