|

|

|

|

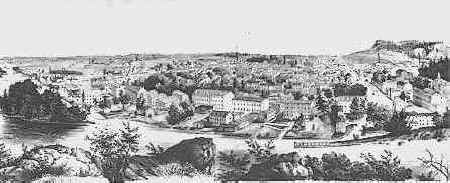

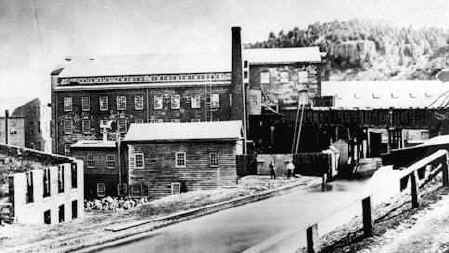

S.U.M. Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures Alexander Hamilton initiated America's first planned industrial center in 1791. He and a group of investors wished to achieve America's independence from British manufacturers, so they founded the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.) to harness the power of the Passaic River's Great Falls. The authorized capital of the new company was $500,000, an enormous sum for those days. The charter granted by the N.J. State legislature gave the S.U.M. perpetual exemption from county and township taxes and gave the S.U.M. the right to hold property, improve rivers, build canals and raise $100,000 by lottery. Hamilton engaged Pierre Charles L'Enfant, a planner/architect for the city of Washington D.C., to layout the town of Paterson and build raceways to supply water to the planned manufacturing mills. L'Enfant had a penchant for grand schemes and proposals. He visualized a series of radiating roads (a modified version of Washington) for the town. The waterpower system would have a grand aqueduct that would channel water from the Passaic River, across a ravine, and around a hill to the mills. This aqueduct would span the ravine, be large enough for barge traffic, and have a towpath on one side and a carriageway on the other. He also planned a reservoir for water storage to ensure an adequate supply for the mills. The S.U.M. dismissed L'Enfant when work was barely underway because his scheme was considered too ambitious. In his place, the S.U.M. hired Peter Colt, an American, with little engineering experience but a great deal of common sense. He simply dammed up the ravine at one end, creating a reservoir, and sent the water into a single raceway down the hillside to the site of the first water-powered mill. However, before this work was finished, Colt put up a small frame mill in the proposed mill district, because the S.U.M. was anxious to begin spinning cotton. An ox furnished the power needed to turn the wheels. The mill was called the Bull Mill. Then, work began on a bigger mill where printing, bleaching and dying were to be done. This mill was situated on Mill Street. It was built of stone and wood and measured 90 by 40 feet. It was four stories high. A cupola on top housed a bell that called the men to work. Some small fittings of brass and iron were brought from Wilmington, Delaware, the nearest place where such things were made. However, most of the machinery was brought from Europe. A man was given $50,000 with which to bring men and machinery from Europe, but disappeared with the money, never to be found again. Notwithstanding, the mill began to turn out textiles in 1794. The S.U.M. had a more or less turbulent existence in the beginning. In January of 1796, it closed its only mill and ceased to manufacture. Henceforth, the activities of the S.U.M. were confined to the management of its extensive estate in Paterson, including the waterpower rights.

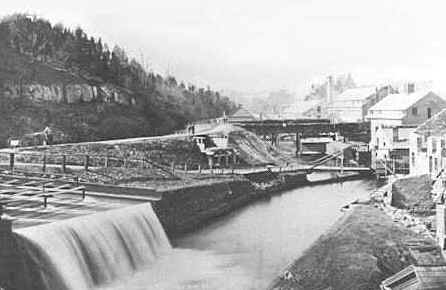

In its ultimate form, the raceway was capable of developing over 2000

horsepower. Land along the raceways was continually being subdivided into lots that were leased for building mills. These leases gave the mill-owners rights to draw water from the

raceways. Water from the raceway was directed by flumes to waterwheels that could be 20 feet in diameter and six feet wide. Power from these waterwheels was then transmitted through shafts, gears, and belts to individual machines within the mill buildings. The water then returned to the river via tailraces. Beginning in the late 1840's, a new form of waterpower device was invented to replace the waterwheels. These turbines, as they were called, were made of iron instead of wood. They consisted of a series of blades mounted on a shaft, called a runner. The runner and blades were enclosed in a steel case. The weight of the water and the flow of the water striking the vanes drove the runner around. Use of the raceway system continued to expand as industries prospered in Paterson. However, by about 1900, it was apparent that the individual water wheels were less efficient than a central station generating hydro-electricity. In 1910, the S.U.M. built the hydroelectric plant that had a maximum capacity of 6500 horsepower, with its four huge turbines generating 21 million kilowatts per year. The S.U.M.'s economic activity fluctuated between periods of boom and depression, occurring in approximately 20-year intervals. Interspersed were depressions, strikes, unemployment, and influxes of immigrants. One fortunate aspect of the adaptable re-use design of the mill buildings was that they survived these turbulent changes. The large scale of the buildings, as well as their simple floor plans and structure, accommodated a variety of uses. What remains in the Great Falls / S.U.M. National Historic Landmark District is an architectural and archeological history that traces the growth and progress of industry from 1791 to the present. Paterson is both the oldest and only manufacturing center that offers such an extensive catalogue of industrial architecture in America. For a great synopsis of the history of the S.U.M. and Paterson, view "Introduction to the New Jersey Historical Records Survey, Project Copy of the Calendar of the S.U.M. Collection of Manuscripts" |

For instance, the lease to John Parke, on November 1st, 1807, gave him rights to draw 15 square

inches of water from the raceway onto his lot, for which he was to pay $100 per year.

For instance, the lease to John Parke, on November 1st, 1807, gave him rights to draw 15 square

inches of water from the raceway onto his lot, for which he was to pay $100 per year.