|

|

|

|

BACKGROUND | THREE GREAT REPORTS | THE CORPORATE EXAMPLE | THE DUEL

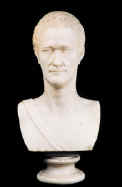

Alexander Hamilton THE CORPORATE EXAMPLE: Alexander Hamilton not only encouraged private manufacturing, he provided an example of how corporations could be organized by individuals to develop manufacturing on a large scale. He established a model, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufacturers, also known as the S.U.M. This type of business enterprise forged the basis of American capitalism. Earlier, Hamilton had proposed to Congress that the federal government spend $1 million, which was two percent of the national debt, to build a "national manufactory." Hamilton knew this idea would be rejected, so he initiated America’s first planned industrial center in 1791 with private funds. He and a group of investors chose a site where they could harness the power of the Great Falls of the Passaic River in the state of New Jersey. The enormous height of the falls, 77 feet, and the surrounding terrain had characteristics that were essential for the utilization of waterpower at that time. The New Jersey Legislature granted a charter to the S.U.M., which was signed on November 22, 1791 by Governor William Paterson. It became the first large business corporation in America. The new town was called Paterson and construction of a water raceway system began in 1792. It was the first attempt within the United States to harness the enormous power of a major river. Paterson, along with other manufacturing centers across New England, eventually created great textile wealth from the combination of enterprise, labor, waterpower, machines, raw fiber, and capital gained from foreign commerce.

Capitalism: Colonial American laws and institutions held that land was the legitimate source of wealth and status. The property qualifications for voting and office holding were land and improvements. Except in parts of New England, most of the land belonged to the few; in the older areas of the South, 10 or 15 percent of the white families owned upwards of two-thirds of the land. Hamilton had nothing against a hierarchical and deferential social order. He thought such an order natural, desirable, and, in any politically free society, inevitable. Furthermore, he abhorred the leveling spirit. But his detestation of dependency and servility was stronger yet, for those were contrary to his very idea of manhood, and the system of pluralistic local oligarchies made everyone dependent upon those born to the oligarchy. He hated the narrow provincialism that the system nourished and fed upon; and he resented, as only a natural-born outsider can, the clannishly closed quality of the system. Most objectionable of all was that the system failed to reward industry—industry in the sense of self-reliance and habitual or constant work and effort. His crucial idea was to enable and encourage individuals so long held back to invest in themselves and their ideas. He made it possible to measure worth and achievement in terms of money. One worked for oneself through the marketplace. Each newly sovereign individual could prosper if he proved energetic and hard working. Each individual became a free man; each having the right to seek his own happiness. Hamilton’s mission was to enliven man’s possibilities. It was a mission premised on human dignity, a dignity that made each man an equal being.

Federalists vs. Republicans: After Jefferson's victory in 1800, however, the Republicans were compelled by circumstances to continue with the Hamiltonian nationalistic outlook. Jefferson proved to be a pragmatist who could appreciate the benefits of an energetic central government. His administration began to use the Hamiltonian financial system effectively. The Bank of the United States thrived and business went on much as it had before. Public opinion turned back again toward the broad use of national powers to stimulate and direct economic development. The public came to believe that Hamilton's financial measures were designed for the common good and were consistent with the requirements of a free federal republic. Preference for Jefferson's doctrine of decentralization and states' rights gained momentum, however, during the decades leading up to the Civil War especially during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Southerners asserted their states' rights as resistance to any interference in their use of slavery. On the Union side stood the stability and strength of the federal government that Hamilton insisted upon for his entire career. The Union shared Hamilton's outspoken opposition to slavery. The outcome of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery proved the merit of the Hamiltonian way, leaving the South and simple agrarianism behind the rest of the nation in its steps toward greatness. After the war, the United Sates benefited from an era of great industrialization and innovation. Reconstruction and westward expansion brought about increasing capitalist enterprises. Hamilton's legacy enjoyed an unprecedented ascendancy. As he had expected, the United States became the richest, most powerful and freest nation in the history of the world. BACKGROUND | THREE GREAT REPORTS | THE CORPORATE EXAMPLE | THE DUEL |

Hamilton

was a brilliant young reformer. He helped transform America into a nation that

promised a new way of life for its citizens. During his position as the first

Secretary of the Treasury, money became the universal measure of social

position, a neutral arbiter. It transformed the established economics, made

society fluid, and made industry rewarding and necessary. He made it possible

for men and women to succeed in life without a dependency on birthright, family

connections and ownership of land. He put into place a system of law and finance

in which existing rigid social forms of power over people’s lives were

diminished. Hamilton believed that not only was the existing elitist social and

economic order unjust, it also bred laziness.

Hamilton

was a brilliant young reformer. He helped transform America into a nation that

promised a new way of life for its citizens. During his position as the first

Secretary of the Treasury, money became the universal measure of social

position, a neutral arbiter. It transformed the established economics, made

society fluid, and made industry rewarding and necessary. He made it possible

for men and women to succeed in life without a dependency on birthright, family

connections and ownership of land. He put into place a system of law and finance

in which existing rigid social forms of power over people’s lives were

diminished. Hamilton believed that not only was the existing elitist social and

economic order unjust, it also bred laziness.  In calling both Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson into his cabinet, George

Washington acquired an explosive combination of talents. Although both had

exceptional qualifications for high office that were beyond question, the new

government mainly followed Hamilton's course. The gathering opposition to

Hamiltonian policies, headed by James Madison, began to turn to Jefferson for

leadership. In the presidential election of 1800, a majority of voters in the

nation abandoned Hamilton and the Federalists, believing that it was the road to

oppressive nationalism and financial oligarchy. Jeffersonians embraced the free

pursuit of private interest policed by the states and regulated by the central

government only in those special cases where the national interest was obviously

of first importance. Their main principle was individual liberty, whereas

the Federalists espoused government discipline as a channeling device for

national development. Both sides of the debate formed an ongoing dialogue

that continues to this day.

In calling both Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson into his cabinet, George

Washington acquired an explosive combination of talents. Although both had

exceptional qualifications for high office that were beyond question, the new

government mainly followed Hamilton's course. The gathering opposition to

Hamiltonian policies, headed by James Madison, began to turn to Jefferson for

leadership. In the presidential election of 1800, a majority of voters in the

nation abandoned Hamilton and the Federalists, believing that it was the road to

oppressive nationalism and financial oligarchy. Jeffersonians embraced the free

pursuit of private interest policed by the states and regulated by the central

government only in those special cases where the national interest was obviously

of first importance. Their main principle was individual liberty, whereas

the Federalists espoused government discipline as a channeling device for

national development. Both sides of the debate formed an ongoing dialogue

that continues to this day.